A draft version of the honey bee genome has been made available to the public - a move that should benefit bees and humans alike.

The honey bee (Apis mellifera) is multi-talented. It produces honey, pollinates crops and is used by researchers to study human genetics, ageing, disease and social behaviour. "Without bees and pollination, the entire ecosystem would crumble," says Richard Gibbs, who led the sequencing effort at the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Its genome is about one-tenth the size of its human equivalent, containing about 300 million DNA base pairs. Because the genome is relatively small, genes should be easy to identify, says bee researcher Steve Martin from the University of Sheffield, UK. Many of these will be similar to their human counterparts, he says.

The bee genome may also help us understand the genetics of ageing and social behaviour, says Martin. Queen bees, for example, can live five times as long as their subordinates. Unpicking their genes may help researchers understand why.

Honey monsters

The genome's publication is good news for beekeepers and victims of bee stings alike.

Across the globe bees are threatened by a pesticide-resistant mite called varroa. The bug, which has spread from Asia, weakens the insects, making them susceptible to fatal infections. "The new information may help researchers generate varroa-resistant bee strains," says Claire Waring, editor of the beekeeping journal Bee Craft. Such insects would be healthier and produce more honey.

It may also help us understand aggressive bee behaviour, says Gibbs. Stroppy swarms of Africanized bees can attack and kill people and animals. The genome may reveal the genes linked to bad bee behaviour. "This may help us deal with the problem," he says.

Researchers have deposited the draft sequence with GenBank, a public database run by America's National Institutes of Health. It will also be published on European and Japanese databases.

The project began in 2003, when the US Department of Agriculture and the National Human Genome Research Institute donated more than US$7 million. This is the first time that the amassed sequence data have been made publicly available.

Ultimi Articoli

Lombardia: prima legge regionale sull’Intelligenza Artificiale — approvato il progetto per ricerca, imprese e pubblica amministrazione

Triennale Milano — gli eventi dal 3 all’8 marzo 2026 tra spettacoli, incontri e musica dal vivo

Roma — Malattie rare, ASL Roma 1 presenta il nuovo portale e iniziative di prossimità per i pazienti

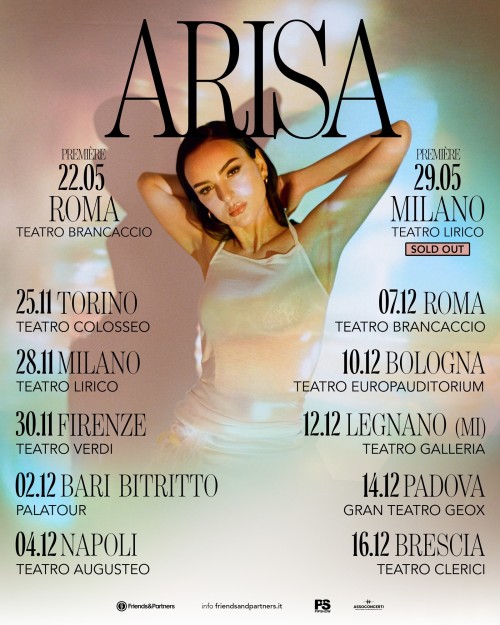

Sanremo — Arisa in gara con Magica Favola, sold out a Milano e tour nei teatri da novembre

Fender personalizzati ad alte prestazioni — la nuova protezione smart e sostenibile per barche e navi

Milano: a marzo partono i lavori in via Bramante, Torino e Cesare Correnti — riqualificazione strade e binari

Arisa: Magica Favola — tra le prime cinque a Sanremo — online il video e live a Roma e Milano

Levante: esce “Sei tu” dopo l’Ariston — nuovo singolo e tour 2026 nei club italiani

UN LETTO PER DUE: 35 ANNI D’AMORE TRA PASSIONE, TRADIMENTI E RIMPIANTI AL TEATRO SAN BABILA DI MILANO