Natural selection picked out the chemical basis of genetic information transfer probably because it was the best of the available options for ensuring fidelity in reading and copying information.

Dónall Mac Dónaill of Trinity College, Dublin, has worked out that DNA code is like the parity code that information technologists use to minimize the probability of making mistakes1.

Genetic information stored in DNA is read out - transcribed - every time living cells make a new protein molecule to perform some cell function. And this information is copied onto a new strand of DNA when a cell divides.

The consequences of wrongly read or copied information can be disastrous. Malfunctioning genes can cause diseases and defects. Errors can occasionally have beneficial effects - they create the mutations that drive the evolutionary process - but they are usually detrimental.

So cells have evolved molecular machinery for checking transcription and replication. This greatly reduces the chances of errors, but does not eliminate them. Mac Dónaill says that there is another mechanism for detecting errors - in the chemistry of DNA itself.

Chemical code

DNA's double helix consists of two twisted molecular strands bound together by hydrogen bonds. The four building blocks of each strand are called nucleotides. Their names are adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine, and are abbreviated to A, T, C and G.

These four stick together very selectively: A to T, and C to G. A binds to T by two hydrogen bonds, and C sticks to G by three. Other pairings are possible, but they distort the DNA strands. Error-correcting enzymes look out for such mismatches when DNA is replicated.

Mac Dónaill argues that the nucleotides' pairings are a kind of code. Each hydrogen bond has two components: chemical groups called donors and acceptors. If we denote a donor as 1 and an acceptor as 0, then C encodes the pattern 100, and G is 011.

In other words, each nucleotide can be represented as a short sequence of binary code, like the 1's and 0's used to record information in computers.

There is one more element in this code. A and G belong to a class of molecule called purines, and T and C are pyrimidines. Each pairing involves a purine and a pyrimidine. We can denote a purine by 0 and a pyrimidine by 1. Then C becomes 100,1 and G is 011,0.

Represented in this way, says Mac Dónaill, the permissible combinations of A,C,T and G correspond to what computer scientists call a parity code. Each nucleotide has an even number of 1's - it is said to have an even parity.

This makes it easier to spot errors such as non-natural nucleotides. If the error changes any one digit in a nucleotide, its parity changes from even to odd. Odd-parity nucleotides are clearly wrong.

When life first emerged from simple molecular constituents, says Mac Dónaill, "selective pressure should have favoured parity-code-structured alphabets".

In other words, genetic information became encoded in A, T, C and G, and not in the several other types of purines and pyrimidines that must have coexisted with them, not just by chance but a result of the parity code that this subset of molecular building blocks forms.

Other combinations of these kinds of molecule could produce other parity codes, but there are chemical reasons why these combinations wouldn't have worked so well.

PHILLIP BALL

Ultimi Articoli

Lombardia e Fiandre — intesa per collaborazione su semiconduttori, manifattura e ricerca

Michele Basile dalle star dei social al palcoscenico debutta con “Stai Karma” al Manzoni di Milano

Al Teatro Manzoni di Milano una serata che cambia prospettiva: Luca Mazzucchelli porta in scena “Terapia al contrario”

Pinocchio siamo noi: al Teatro Menotti il manifesto teatrale sulla fragilità

UOMINI E TOPI : IL SOGNO FRAGILE DELL’AMICIZIA al Teatro San Babila di Milano

Lombardia: prima legge regionale sull’Intelligenza Artificiale — approvato il progetto per ricerca, imprese e pubblica amministrazione

Triennale Milano — gli eventi dal 3 all’8 marzo 2026 tra spettacoli, incontri e musica dal vivo

Roma — Malattie rare, ASL Roma 1 presenta il nuovo portale e iniziative di prossimità per i pazienti

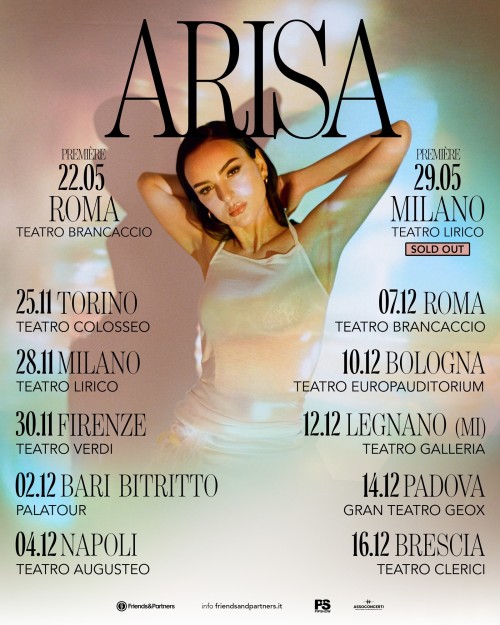

Sanremo — Arisa in gara con Magica Favola, sold out a Milano e tour nei teatri da novembre